Gig Reviews

Thy Catafalque

Stengade, Copenhagen, DEN - 6/4

Album Reviews

The Pirate Bay: Copyrights or Human Rights?

Previous Next

author AP date 14/03/09

On May 31st 2006, the offices then housing The Pirate Bay's servers were raided by Swedish police, prompted by allegations by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) of copyright violations, causing the popular torrent tracker to go offline for three days during which the entire European internet traffic reportedly dropped by 40%. Following a two-year investigation, on January 31st 2008, Swedish prosecutor Håkan Roswall filed charges against four of the individuals behind The Pirate Bay, Gottfrid Svartholm Warg, Peter Sunde Kolmisoppi, Fredrik Neij and Carl Lundström, for allegedly assisting in copyright infringement and in making copyrighted material available online. The charges are supported by a consortium of intellectual rights holders led by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI). One of the most high-profile of its kind, the two-week trial, dubbed by The Pirate Bay as the Spectrial (a portmanteau of spectacle and trial) began on February 16th and ended on March 3rd, with the final verdict expected on April 17th. In this article I will look at some of the important points raised during the trial, commenting on them where appropriate, and discuss the issue of illegal file-sharing with emphasis on the music industry. Please be aware that much of the discussion reflects a personal opinion and that Rockfreaks.net in no way participates in illegal activities of any sort. Readers are encouraged to think critically about the content and respond with their own views in comments at the bottom of the page.

As TorrentFreak has already provided an in depth narrative about the day-to-day progress of the trial, I see no reason to rehash it great depth here, but will rather attempt to bring across the most important issues from the two week spectacle. The quintessential aspect of even attempting to understand and evaluate the trial, of course, is to understand how BitTorrent technology actually works - something which the prosecution failed to comprehend, resulting in 50% of the charges against The Pirate Bay to be dropped already on the second day of the trial. Håkan Roswell attempted to use as evidence screenshots of a number of .torrent files, but failed to adequately explain the function of a Distributed Hash Table (DHT), which allows for so-called trackerless torrents. The flaw in the evidence was pointed out by Fredrik Neij who went on to explain that the prosecution misunderstood the technology and told the court that the evidence in no way shows that the .torrent files actually used The Pirate Bay's trackers in the first place. As a result, Roswell was forced to drop all charges relating to assisted copyright infringement, so that the remaining charges are simply with regards to making copyrighted content available. So to avoid misinterpreting BitTorrent technology, let's take a look at how it actually works.

BitTorrent is a peer-to-peer (p2p) file sharing protocol most commonly used for distributing large files over the Internet, and is estimated to account for some 35% of all Internet traffic. The protocol works initially when a file provider makes data available to the network by creating a BitTorrent (.torrent) file, which contains metadata about the file(s) to be shared and the tracker that coordinates its distribution. What essentially happens is that the file provider treats the file as a number of identically sized pieces and creates a checksum (used for detecting errors that may have been introduced during storage of the data) for each piece using a secure hash algorithm, which is then recorded in the .torrent file. This known as seeding, and enables others, peers, to connect and download the file. When a peer eventually receives the pieces, the checksum of each piece is compared to the recorded checksum to check that the piece is error-free by a BitTorrent client (a program that manages torrent downloads and uploads using the BitTorrent protocol). Once a peer has downloaded the file, it becomes available for other peers to download thus creating another seed for it. Depending on the number of seeds for a given file, this technology allows peers to download the file from multiple locations concurrently, exponentially increasing the likelihood of a successful download and significantly reducing the original distributor's hardware and bandwidth resource costs. In addition, the protocol provides redundancy against system problems and reduces dependence on the original distributor.

The Pirate Bay is a Swedish web service that indexes and tracks .torrent files. As such it provides a search engine to its database of .torrent files (not the actual files) and a BitTorrent tracker, which coordinates communication between peers attempting to download the payload of the torrents. The Pirate bay publicizes its tracker's URL, and the site's users then upload torrents to the index with the tracker's URL embedded in them, providing all the features necessary to initiate a download. That is, The Pirate Bay is no more responsible for the content hosted on its servers than a search engine like Google, which incidentally provides a far more comprehensive list of links to torrents hosted on virtually every one of the hundreds of BitTorrent trackers that exist. Please take note of this important fact, as it has been revisited a number of times during the actual trial.

Further highlighting the prosecution's, and indeed probably the entire music industry's confusion as to how BitTorrent technology, and particularly trackers like The Pirate Bay work, is their belief that the website somehow participates in the exchange of copyrighted material by users. Carl Lundström's lawyer, Per E. Samuelsson laid the problem out in what has since become known as the King Kong defense. He referred to EU directive 2000/31/EG, which states that he who provides an information service is not responsible for the information that is being transferred; in order to be responsible, the service provider must initiate the transfer. In the case of The Pirate Bay, as just mentioned, the transfers are initiated by users who are physically identifiable people who, as Samuelsson famously told the court, call themselves names like King Kong. He went on to point out that according to legal procedure, there must be a clearly discernible tie between the perpetrators of a crime and those who are assisting in it. What the prosecution failed to show was that Carl Lundström had personally interacted with King Kong, who may very well be found in the jungles of Cambodia.

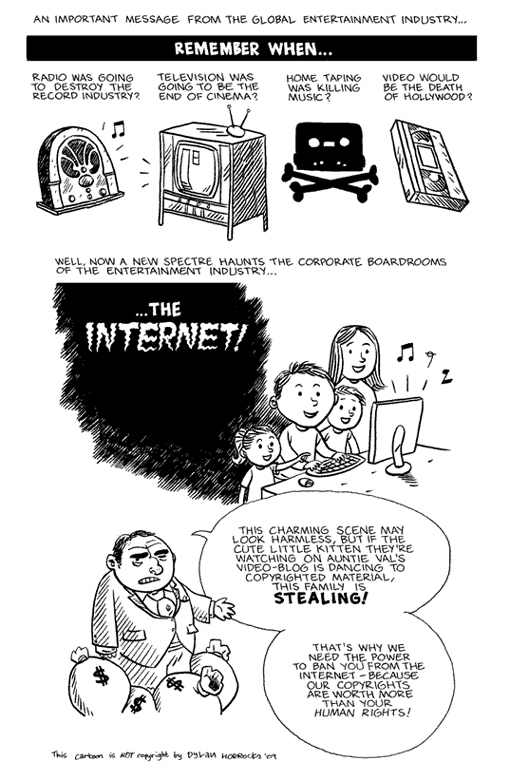

Indeed, the efforts by representatives of the music industry to combat piracy appear more often than not to be misguided. Rather than embrace an emerging technology, organizations such as the RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America) and MPAA prefer to stick to their recurrent suspicion to all things new. Recall that these same organizations once feared then-new technologies like radio and cassette tapes; the digital revolution introduced yet another enemy and history repeats itself. The general strategy now seems to be a combination of muscle-flexing (through a few prominent court cases, such as the Pirate Bay trial), bullying and threatening the little guy they claim to stand up for. While there is no question that distributing copyrighted material without a license is a crime, the methods often used to combat the problem are unacceptable. Case in point: the IFPI and others actually believe the opposite of the directive - or choose to ignore it - and have, unfortunately with some success, pressured several internet service providers around the world to take up unprecedented and morally questionable measures to further their agenda.

One such instance recently sparked outrage when the IFPI took Tele2, one of the largest ISPs in Denmark, to court, arguing that it was aiding in copyright infringement because it allowed its customers to access The Pirate Bay. The judge agreed that Tele2 could indeed be held accountable for the traffic its customers generate, forcing the ISP to block access to The Pirate Bay. Soon after, another major Danish ISP, TDC, also blocked access to the site. In an even more radical move, Eircom, Ireland's biggest ISP, recently also capitulated to the IFPI, agreeing to disconnect users accused of illicit file-sharing via a "3 Strikes" regime. The keyword to take note of here is accused. A similar, guilty-on-accusation law was passed in New Zealand last year, requiring that users be thrown off the Internet based solely on the accusations of those claiming copyright infringement. That such Draconian laws are now emerging worldwide begs the question: how can a commercial organization have the influence to pressure governments into adopting laws that the IFPI probably draws up? It seems unthinkable - until the truth comes out. Organizations like the IFPI, RIAA and MPAA are more powerful in the United States than us Europeans would like to admit, it turns out; so powerful, in fact, that their lobbyists successfully convinced the U.S. government to threaten Sweden with economic sanctions if it refused to comply with the organizations' demands to shut down and persecute The Pirate Bay, which, according to Swedish law, has been confirmed by a number of lawyers to operate within legal confines.

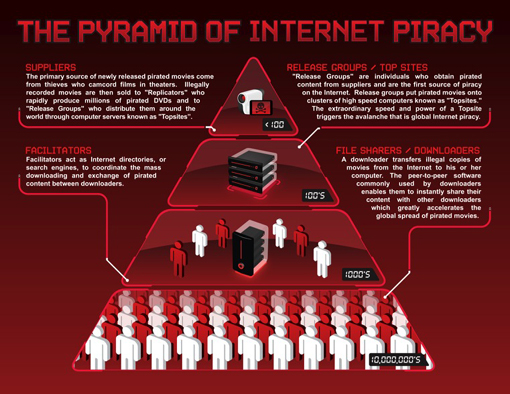

Nonetheless, the four men behind website were taken to court in a media spectacle which, regardless of its outcome, will do little to address the problem of illicit file-sharing and result in more PR fodder for both parties. At best, The Pirate Bay's outspoken defiance in the face of legal threats and the subsequent success in persecuting it has given the IFPI's press releases a "look who's laughing now" edge and earned The Pirate Bay a legion of new fans. What's interesting is that the IFPI and others apparently believe that blocking or shutting down trackers is a major blow for the pirates. Ironically, looking at MPAA's own findings, websites like The Pirate Bay are far from being at the core of the problem. The industry need only to look within its own ranks to find the culprit: the mid-level employee with premature access to music or films. It is no secret that pirates, for the most part, demand quality which copies recorded with camcorders in a cinema cannot deliver. A huge part of copyrighted material found on torrent sites comes from leaked screeners and copies intended for promotional use, and it isn't unreasonable to think that the industries could fathom some way to address the problem internally. Digital watermarks, which now accompany many promotional releases are a step in the right direction.

During the trial, a very interesting and important point was raised by Roger Wallis, Chairman of the Swedish Composers of Popular Music, and later in a blog by Jens Roland (a professional technology forecaster) in response to John Kennedy, the CEO of the IFPI, presenting his view that The Pirate Bay is an extremely damaging force on the global music industry, that what the site offers is just too tempting for people to resist, and that the claim that illegal downloading actually promotes sales is old-fashioned thinking. Wallis argued that illegal downloading caused an increase in the sales of live event tickets and that although there had been a reduction in CD sales in recent years, it would not continue. Wallis went on to explain that while some people download, these same people also tend to buy more CDs than others who don't, and added that downloading was not the sole culprit for declining CD sales, but other things, such as the growth of computer gaming, have an effect too. Roland then continued Wallis' argument in a blog and provided insights as to why the decrease in revenues from music could not be blamed solely on piracy and that in fact piracy's share in the problem is much more minor than widely thought. He argues that the past eight years have seen more changes in the landscape of home entertainment than CEOs of big media companies would like to admit, and that some of those changes have had a massive impact on music profitability - much more so than any amount of piracy. Let's look at his argument in more detail.

As mentioned by Wallis, computer and console gaming has added a competitive third element to the entertainment landscape and beaten both music and movies to the ground. Revenues from music have been reduced by gaming because consumers do not have infinite money, and billions of recreation dollars which used to go almost exclusively into music, are now going into gaming. Also worth mentioning is that new forms of distributable media, most notably the MP3, have become mainstream. MP3s do not degrade over time, making rebuying music a thing of the past and allowing the second-hand market for music to flourish and expand - both of which take their cut from the music industry's revenues. Not to mention the technological innovations that have taken place in the field of music creation itself. Recording hardware and other necessary equipment have evolved to the point where most artists can now afford decent equipment to do their own recording and production, which has not only challenged the traditional need for major record labels, but also spawned thousands of small, specialized studios which offer lower prices, better terms for the artists, and genre-specific expertise.

International trade agreements, which have allowed consumers to buy their music across borders rather than accepting local prices on music based on the relative wealth of nations, rather than the actual value of the product, should not be forgotten either. Furthermore, the World Wide Web has become an omnipresent entity, allowing for cheap distribution of digital music, cutting out corporate music distributors, who, Roland argues, deal in trucks and CD covers rather than bytes and bandwidth. iTunes is a prime example: billions of songs are now purchased digitally, eliminating the need for the big labels' distribution networks. iTunes, by the way, has been very successful in competing with 'free', indicating that most consumers do not want to be criminals but consider the traditional model of the music market obsolete; not to mention that some music does not even become physically available in most countries, and ordering a CD from the United States adds the extra cost of customs tax. A quick read through the interviews on this site will reveal that the smaller acts with no international record deals look the other way when people download their music illegally because they would like to be heard by as many ears as possible and thus develop their careers and hopefully be able to embark on international tours, which, by the way, is what most bands make their money from. "Merch and touring," has been the general consensus in our interviews when we have asked bands how they sustain themselves.

And what about the exponential growth of radio stations, music television networks and other streaming sources of music? These have given fans a huge selection of free (and legal) music options. Satellite radio, DAB and internet radio have made it effortless for people to tune into a channel broadcasting exactly the sub-genre of music that they feel like listening to. Isn't it easy to see how the purchase of music has become entirely optional for the casual listener (and not just because of piracy)? Most importantly Roland points out that the music industry has shot itself in the foot by letting consumers digitally buy single tracks at a time rather than forcing full albums on them. There is a direct correlation between the break-off in album sales and the introduction and increase in single track digital sales. It is clear that the vast majority of consumers never wanted to buy full albums in the first place, and now that this is no longer necessary, countless millions of album sales have turned into one- or two-track transactions, decimating the former revenues from music. This might well be the penultimate reason why the music industry is hurting.

And yet the IFPI continues to clench its fists at services like The Pirate Bay and governments bend to corporate pressure. Both The Pirate Bay and the IFPI see themselves as defending the little guy (for an interesting article on such claims, read this), and where the one seems to stand for copyrights, the other claims to defend human rights in the way of net neutrality. Who is right is for the judge to decide, but one thing remains clear: piracy will not stop until fundamental change occurs in the thinking of the entertainment industry. It is their old-fashioned line of thought that has turned millions of ordinary citizens into organized criminals who, the MPAA now claims, support gang crime and finance terrorism through their actions. What is needed is for the entertainment industry to start looking at viable alternatives to unlicensed file sharing in order to produce the most satisfactory outcome for all stakeholders. Paul Sanders of Playlouder sums the problem up well: "The music business is putting a lot of effort into shouting at ISPs and comparatively little into selling them music." While the entertainment industry refuses to negotiate any kind of compromise that might lessen the salaries of its top bosses, ISPs are forced to worry about blocking content and thereby losing customers. So ask yourself: copyrights - or human rights?

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook